Why migrant hostels?

In my women’s historical fiction novel, Keepers, my protagonists Raine and Teddy meet on a migrant camp (hostel) in 1949. Raine is there because her family had to move to the city from the country for medical treatment for her father. Teddy’s family, and his best mate Alf’s family, are recent immigrants from the bombed-out East End of London. My camp in the novel is a mishmash of the real ones, and I’ve stretched the truth, as it wasn’t until much later that the accommodation was as self-sufficient as I say in the book. But that’s historical fiction! Here, I share some of the ‘true facts’ about the hostels.

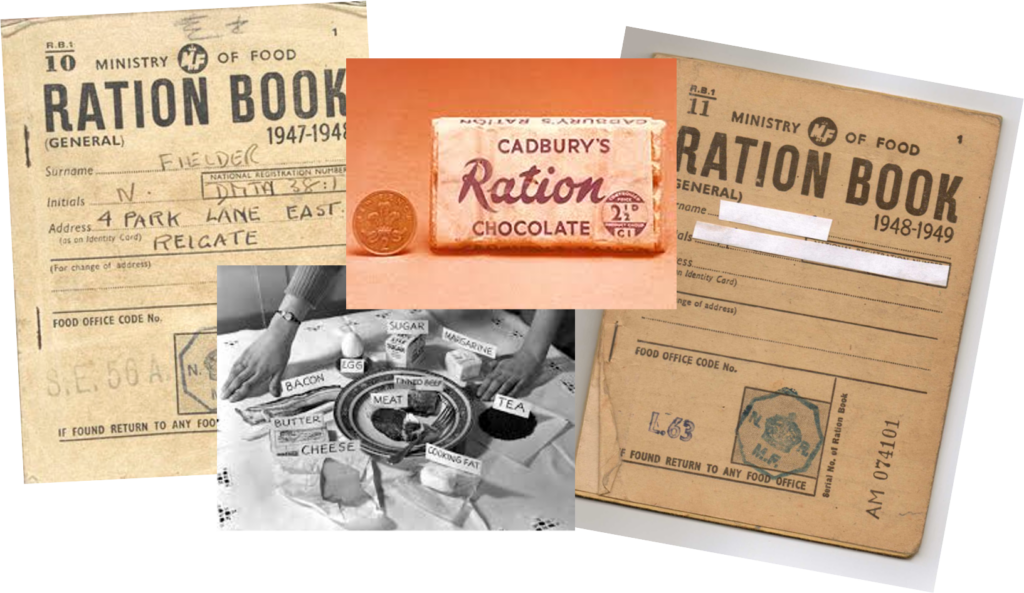

Rationing, queues and cramped housing

Post war Britain was a bleak place, and continued to be so for several years. Many consumer goods and most foodstuffs were still rationed, and the country was under huge economic strain. Even furniture was rationed, with ‘utility furniture’ – introduced in 1942 and available only to newlyweds and those who had been bombed out – all that could be purchased until 1952.

Added to the cost of rebuilding several million homes and public buildings, were the costs of nationalising railways, coal, gas and electricity utilities, and health services. There was also a vast amount of debt to be repaid, and more was added – US war loans weren’t finally paid off until December 2006.

For ordinary people, especially those living in cities, this meant poor, crowded housing – often in non-modernised Victorian terraces – ration coupons and queues. CARE packages from the US were widely distributed, with over 1 million being given out to families to 1956.

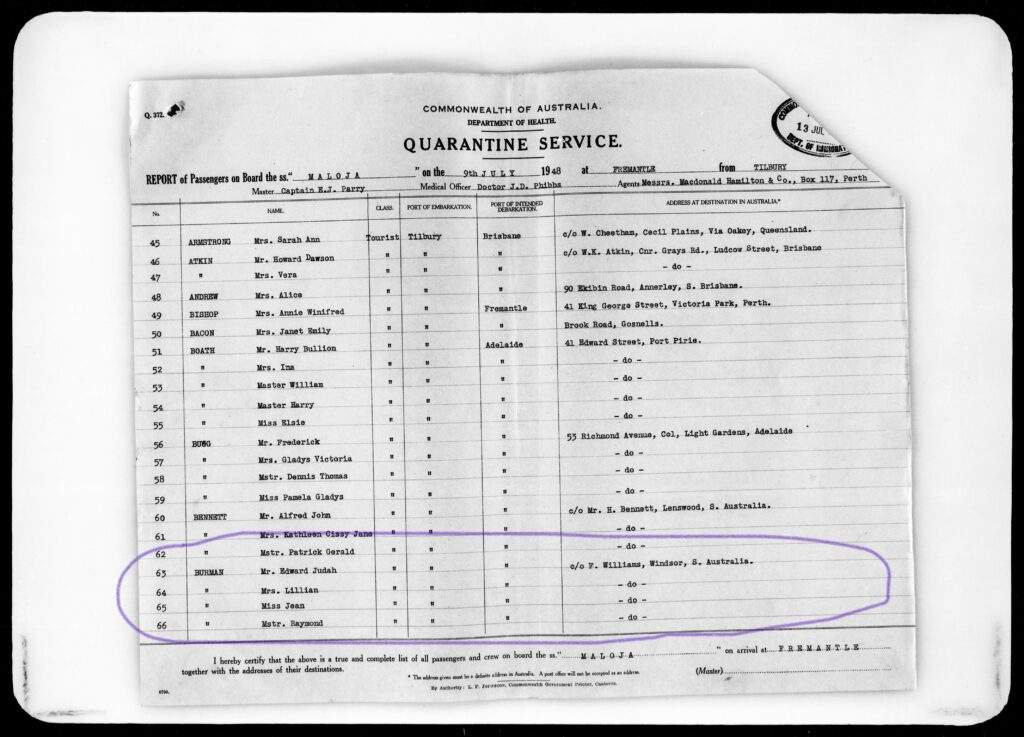

It’s not surprising then, that in 1947, 400,000 Britons registered at Australia House for assisted passage to a better life. It’s also no surprise that the vast majority of British emigrants were from urbanised areas, with a big chunk from London and the South East. This was the area which had taken the brunt of the Blitz, and many had lost homes, family and friends.

The original uploader was Sue Wallace at English Wikipedia., CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Australia – land of tomorrow!

In the meantime, Australia was at a cross-roads, needing people and labour if the country was to take advantage of its natural wealth to prosper. Although at the time immigrants from all over Europe were taken in, British people were seen as the ideal migrant. They didn’t need to learn the language (although some discovered Aussies tended to have a few unique turns of phrase, just as regions in the UK did and do); and by and large they shared Australian cultural values, all being part of Empire. Initially, the Australian government focused on attracting returning soldiers, but quickly launched a marketing campaign to attract worthy Brits to its shores. The allure of posters like this and cheap assisted passages at £10 per head, led to some 1.6 million British people seeking new lives and fortunes in Australia between 1946 and 1982.

These hopeful immigrants travelled four weeks and 10,000 miles to the other end of the world, for a variety of reasons: the warm climate which would banish ailments such as bronchitis or asthma; the promise of bountiful work; clean, modern housing with indoor toilets, and gardens. Or simply a better future for themselves and their children.

What did they find?

Whatever the motivations for leaving everything that was familiar, family and friends, the newcomers’ first experience of the land of tomorrow was a migrant hostel, one of the many hastily created in Australian cities and large towns immediately after the war.

South Australia boasted thirteen migrant hostels which temporarily housed thousands of British migrants (and other nationalities) from 1945 to the end of assisted immigration in 1982. Their purpose was the same: to provide a place for the newcomers to stay while they found jobs, learned their way around, and saved to purchase that great dream – a home of their own. But while the rationale was the same, the physical realities of what migrants met with varied hugely.

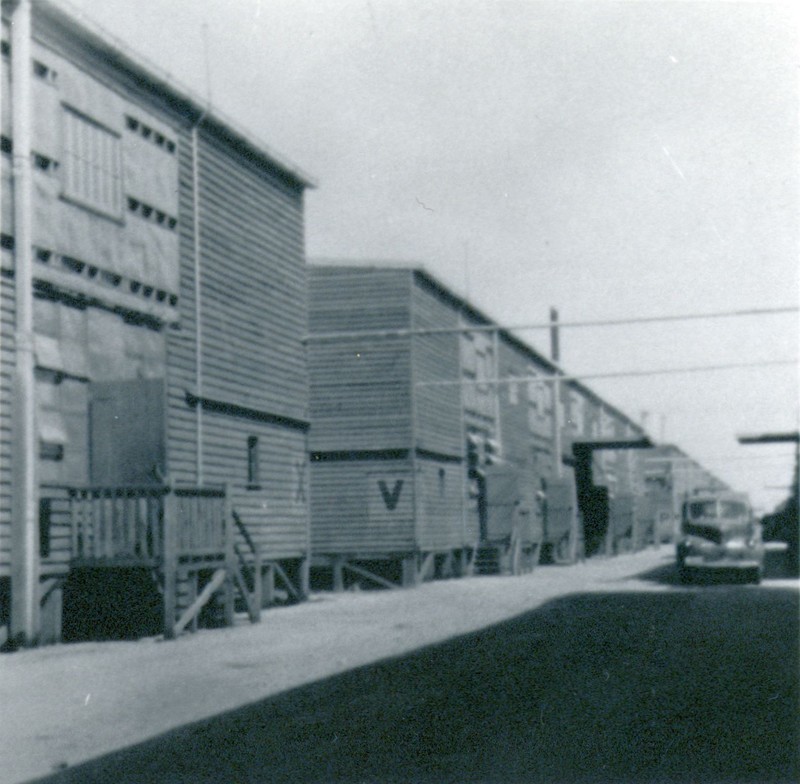

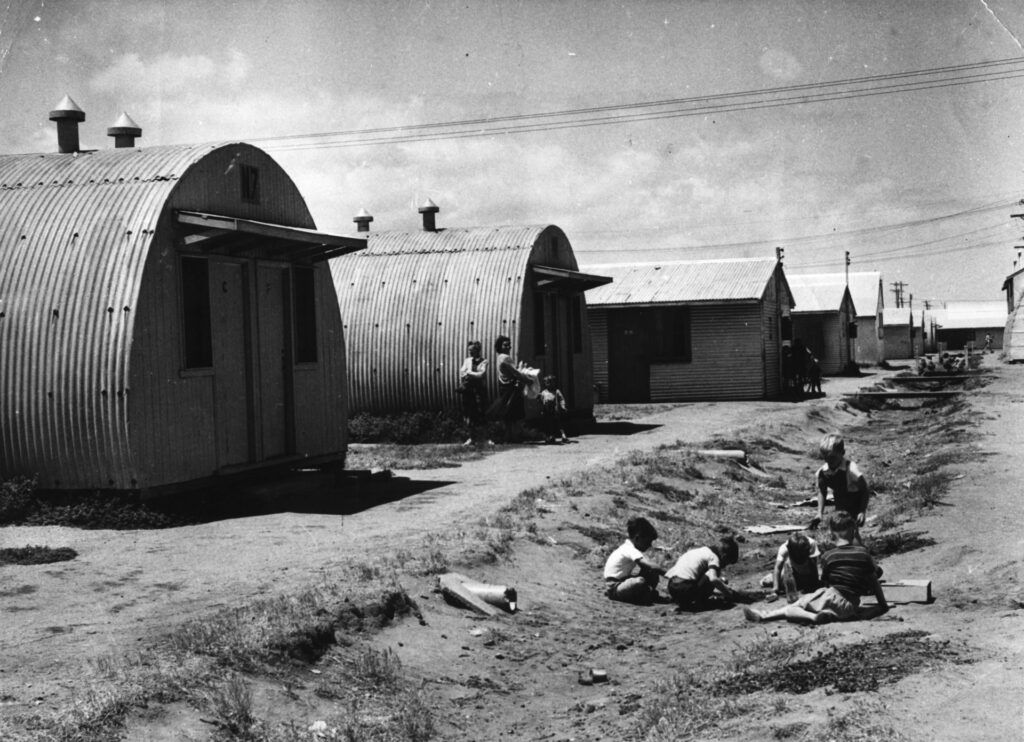

Immigrants arriving from Britain and Europe found Australia unprepared. Makeshift camps were hastily organised in ex-army barracks and even old wool sheds. Conditions were primitive. Early migrants remember Finsbury Hostel (later Pennington), with row upon row of bleak Nissen huts and asphalt floors that softened in the summer heat. Rosewater Migrant Hostel was even worse, with ten old woolsheds divided into 150 tiny rooms by tar paper and chicken wire partitions. History Trust of South Australia, http://www.history.sa.gov.au

In general terms, all the hostels offered similar accommodation in the form of dormitories, for single people and for families, all with flimsy partitions, hot in summer and cold in winter. In some, but by no means in all cases, there were recreation facilities, even a dance hall and movie theatre. Migrants shared bathroom facilities, and there were communal dining rooms where they ate meals cooked for them.

I loved this comment I came across which said the meals at one hostel were ‘basic but plentiful, and edible by their [British] cultural standards’.

No cooking was allowed in rooms, but in those hostels where the food didn’t meet the ‘cultural standards’, many migrants apparently quickly purchased electric frypans.

Location, along with the standard of accommodation, was key in how migrants viewed their temporary homes. Those most favoured were close to facilities and with good public transport, but some, like Gepps Cross, were located in barren, isolated areas. Can you imagine travelling 10,000 miles to be set down on an arid brown plain, in a hot Nissen hut, sharing bathrooms and having to eat what’s given you? Some went back to England – and who can blame them!

Below is a short round-up of the best and the worst of the hostels, and a word about the biggest one.

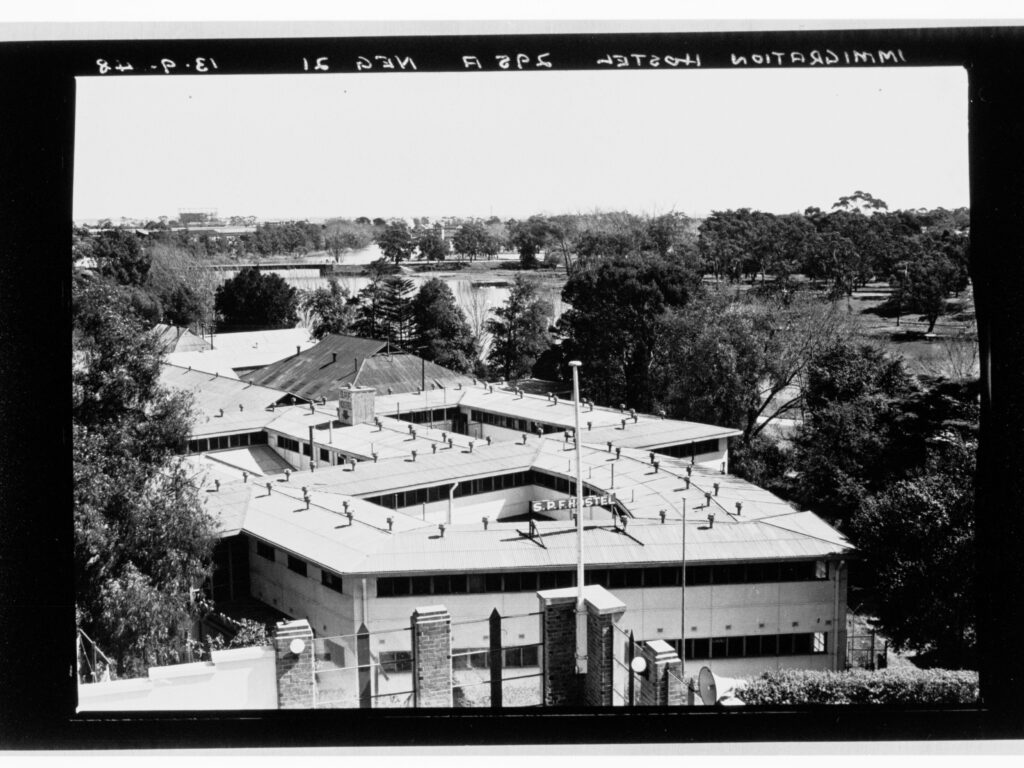

Elder Park

Elder Park, located right at the edge of the city of Adelaide, was considered to be at the top of the pile.

Elder Park Migrant Hostel (formerly the Soldiers Patriotic Fund Hostel) 1948.

South Australian Government Photographic Collection GN14940 and

Dinner time at the Elder Park migrant hostel, c.1948

History SA. South Australian Government Photographic Collection, GN14993

Newcomers to Elder Park slept in dormitories housing singles or families, with minimal furniture – a bed, a table, a lamp, a wardrobe. It was simple, but clean. What made it highly attractive was its location, right on the edge of the city. For the adults, there was easy access to facilities such as the railway station, banks and other businesses, which helped with job hunting and getting settled in. City shopping too, and the market, and entertainment such as movies and sporting events, were all within walking distance.

The children loved it, as they could play in Elder Park itself, and swim in the River Torrens, jumping off the Weir, mixing with the local children.

‘We were impressed … it was good, it was clean … beautiful dining room, and we didn’t have to cook …And they had a beautiful lounge full of chairs, settees … and a nice verandah outside where you could sit in the sun, and the sun was beautiful, never seen anything like this … the kids could go into the park … they’d never seen a black swan …’ (1)

A ‘spartan’ but positive introduction to their new country for those lucky enough to be allocated Elder Park.

Glenelg Hostel was also popular because of its proximity to the beach – beaches being one of the key selling points in the Australian government’s marketing campaign. The suburb itself also reminded many of ‘home’, especially the main shopping street, Jetty Road, with its Victorian shops similar to many a High Street in the UK.

It wasn’t all black swans and beaches for the newcomers. Far from it.

The worst of the hostels was Rosewater, located in Port Adelaide. Accommodation here was in former woolsheds, hastily ‘renovated’ to basic standards. They were extremely hot, and the ceilings were made of wire mesh which allowed great views of rats and other vermin scurrying overhead at night. Charming.

https://sahistoryhub.history.sa.gov.au/places/rosewater-migrant-hostel

It wasn’t only the sub-standard accommodation which was problematic, but the lack of decent public transport and other amenities which made it difficult for migrants to search for jobs and access other facilities. Rosewater was hated with a passion!

‘I remember sitting in the little room by the table and I said, ‘Well, we’re not in Australia, Mum and Dad, until we get out of here!’

Bill Gordon, Rosewater hostel 1950, interviewed 2009

https://sahistoryhub.history.sa.gov.au/places/rosewater-migrant-hostel

‘Arrived at Rosewater in 1951 after spending a few months at Bathurst in the Blue Mountains. My mother was devastated when she saw where we were going to have to live and so were a lot of the other families on the bus when we arrived. My father was one of the migrants who stopped paying rent and they hired a lawyer and took the Commonwealth Hostels to court.’

https://sahistoryhub.history.sa.gov.au/places/rosewater-migrant-hostel

Rosewater was closed in 1953 and the residents moved to other hostels, mainly the biggest one at Finsbury Park.

Here’s a quaint snippet of history –

Rosewater was never meant for British migrants, but for Europeans – mostly displaced persons who were apparently expected to be grateful for whatever they got. It was used for Britons because of shortages elsewhere. The Europeans had a lucky escape

Finsbury Park (Pennington)

Finally, a brief word about one of the major hostels, Finsbury Park (later Pennington). This was purpose built in 1949 and was ‘a mixture of galvanised iron and corrugated asbestos huts, Nissen huts and Romney huts from England, and Quonset huts …. these military buildings were used due to the acute shortage of building materials. … People were allocated sections of the huts, divided to create something like flats. Rooms were simply furnished. There were communal buildings for toilets, showers, laundry and dining, and large Nissen huts were also used for recreational activities such as dances, sporting activities and film nights.’(1)

This is much what I had in mind for the setting of the ‘camp’ in Keepers – rows of Nissen huts, set in a flat, brown wilderness.

Here’s an insightful comment by one former resident:

‘Mum, Dad, my sister Diane & I arrived in late 1959 & were given one of the tiny flat-roofed huts. The floor was bitumen & you could just squeeze the beds into the bedrooms & not much else. When the summer came the fridge sank into the bitumen floor- no aircon of course in those days. If you wanted to make a cup of tea, you had to turn off the fridge first or the fuses blew & showers were in the concrete shower block at the end of the row of huts. All meals happened in the nissan hut canteen & the ground all around the huts was barren. We had no swings or grass or trees that I recall & it was hot, hotter than anything we had known in our lives. The contrast with the UK was total.’ (1)

If you’re interested in exploring further, the two resources below provided much of the information for this article, the quotes and the pictures. The SA History Museum site looks at each of the hostels, and has a blog where former residents comment. Most are from later than when Keepers is set, but it’s all very fascinating.

You can buy Keepers here.

(1) Quotes are from ‘British Migrants in Post War South Australia’ by Justin Antony Madden https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/97969/2/02whole.pdf

or

https://sahistoryhub.history.sa.gov.au/places